25 December 1914 - Night Hawk, Eli, Gem, Therese Haymann

At noon on Christmas Day the minesweeper No.57, formerly the Grimsby trawler Night Hawk, hit a mine three and a half miles off Scarborough. She sank inside ten seconds. Six crew members died, but seven survivors were picked up by adjacent mine sweepers. Five of the six crew killed went down with the ship, but one, Chief Engineer, Albert Chappell succumbed to wounds while being brought ashore.

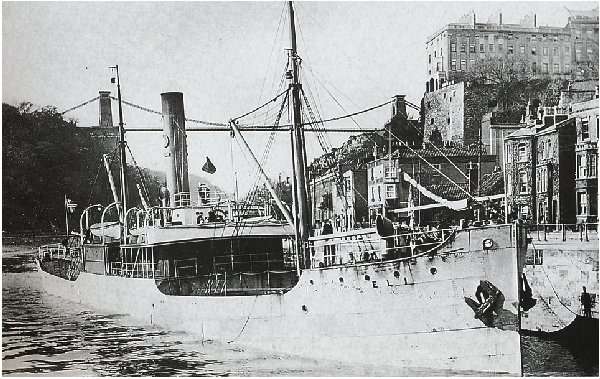

Night Hawk, 25 December 1914

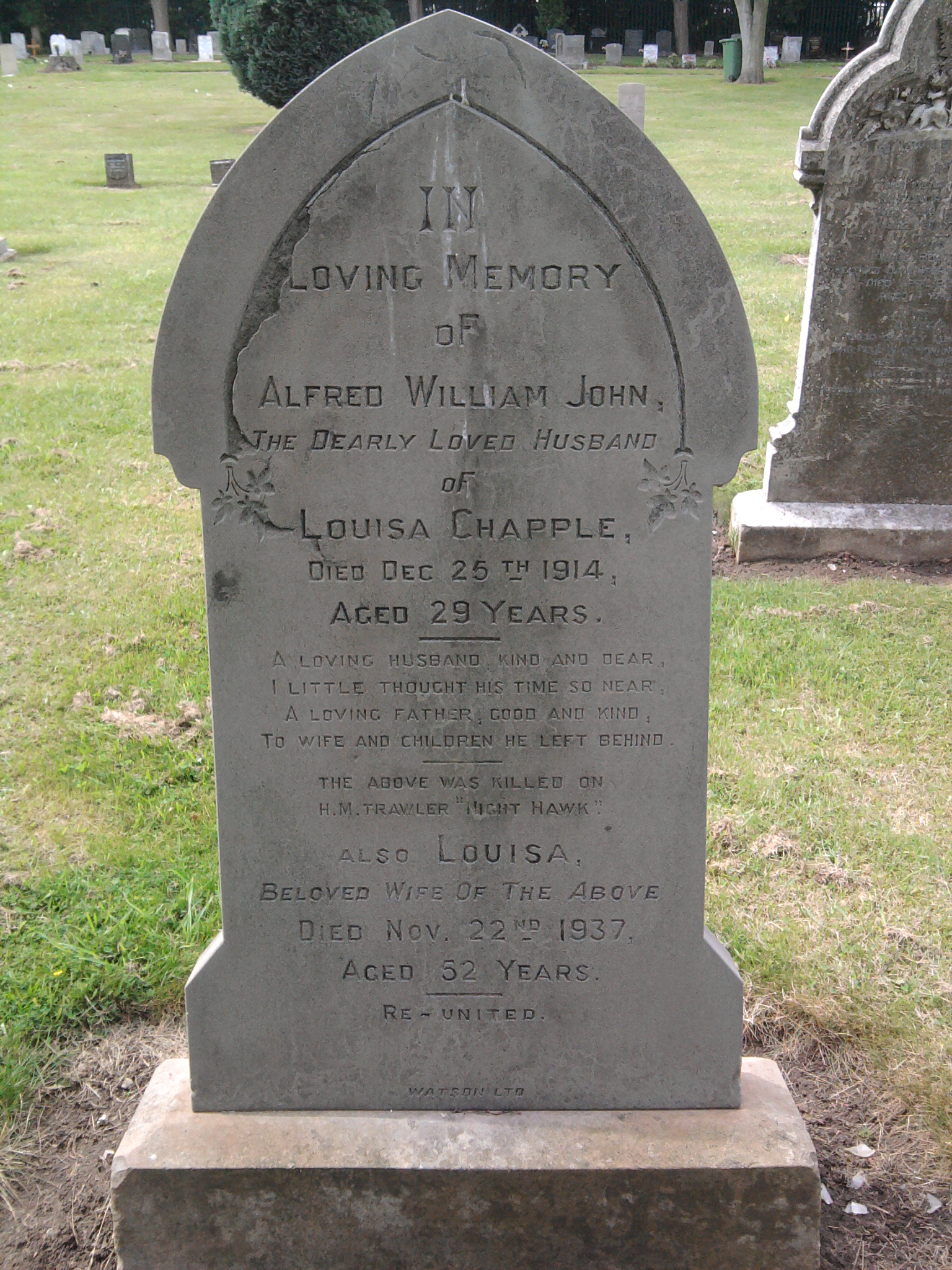

At noon on Christmas Day the minesweeper No.57, formerly the Grimsby trawler Night Hawk, hit a mine three and a half miles east of Scarborough. She sank inside ten seconds. The skipper Harry Evans described the detonation as being akin to hitting a rubber ball because of the deadening concussion. He reported that the 'whole bottom of the ship fell out with her engines and all hands that happened to be below'. Evans was blown clear of the ship by the force of the explosion. Six crew members died, but seven survived, one of the boats officers, Lt. William Senior, rescued most of them from using a life raft which he sculled through the icy water. They were picked up by adjacent mine sweepers. Five of the six crew killed went down with the ship, but one, twenty-nine year old chief engineer, Alfred Chapple of Cleethorpes, succumbed to wounds while being brought ashore. He is buried at Cleethorpes Cemetery.

The Scarborough Mercury reported on the inquest into the loss of the Night Hawk and the death the chief engineer Alfred Chapple. The Scarborough coroner said that the Night Hawk came into contact with a submerged mine. Several of the men were blown completely out into the sea by the explosion, and some sank with the ship. 'If his information was right, these mines which had been floating about in the Bay were laid down by the enemy ships at the bombardment. That made the bombardment all the more terrible and ruthless, and all the more disgraceful. That made the bombardment more grievous and more brutal. It could not be said that the deceased was a combatant, because he was engaged on a work purely and simply to protect those using our harbour or who might be passing along the coast'.

Harry Evans, of Grimsby, skipper of the Night Hawk, stepped into the box with his forehead heavily bandaged, he stated that he had been engaged in mine-sweeping off Scarborough since twenty-four hours after the bombardment. They were sweeping north and south, between Flamborough Head and Whitby, each way. The first day they began three miles off the land, and had gone four, five to five and a half-miles eastward.

‘We left Whitby at 7 a.m. on Christmas Day working southward. We were three and a half to four miles from Scarborough when we struck this mine, which exploded at once. If was like a deafening concussion as if we had struck a rubber ball. I think the whole of the bottom must have been knocked out. Everything was blown to pieces. From the stern to amidships was almost completely blown up.

‘There were two stokers, the second engineer, the steward, and the deck hand below. We knew nothing about them. In seven or ten seconds after the explosion she went down. Those below must have fallen through the bottom with the machinery, and it would be instant death. Those of us on deck were either knocked into the water or taken under by suction. With the exception of myself no one was injured of those on deck, and my injury is only superficial. When we got into the water we would be from fifty to sixty yards apart. There were several other ships sweeping behind us. I think it would be twenty-five minutes to half an hour before assistance arrived. We were struggling in the water that time.’

Relying to the question bearing upon the arrival of the rescue parties, witness added: ‘You cannot run other vessels into danger where one has come to grief. The only thing you can do is to send small boats out, and that is how we were picked up. I remember nothing till we returned to the harbour. They tell me I was walking about on the ship whose boat rescued me, but I don’t remember anything about it. It was bitterly cold. We each had on a life-belt, a life-jacket, and a life-collar.’

The Coroner: ‘Have you picked up many mines?’

‘We keep having a go. You can hear them going off pretty well, I think, at Scarborough. If the wire strikes the object it is gone. If they come to the surface we fire at them.

Moving onto the death of Alfred Chappell, his fellow shipmate Felix Bee of New Cleethorpes, Grimsby, stated they were in the water twenty minutes to half an hour as near as he could tell. The deceased did not appear to be injured when picked up, and apparently died from exhaustion. He was married and had a wife and four children. A verdict was returned of death from the effects of shock and exhaustion following the explosion of a mine.

Crewmen killed on HMT No.57, Night Hawk

Chief Engineer, Alfred Chapple (29), Cleethorpes

Trimmer, Joseph Church

Trimmer, Arthur H Hearne (25), Cleethorpes

Deck Hand, George H Hubbard (21), Grimsby

Engineman, William H Rowbotham (28), Cleethorpes

Cook, Thomas H Shearsmith

In 1973 an inshore trawler working out of Scarborough caught in her nets part of a bow section of a steam trawler. It was discerned that the wreckage was from the Night Hawk, the section of bow was placed on display in a small museum at Scalby Mills. Chris Baker of Filey SAA wrote that the Night Hawk was ‘a well decayed wreck, but with a bit of a fairly intact bow section, with some sort of brass scuppers. There is one, average sized, single boiler. The rest of wreck is more of less flat to the seabed’.

The grim harvest of the mines continued. The Glasgow steamer the Gem was carrying a 460-ton cargo of salt cake from Mostyn to the Tyne. Near when the Eli had earlier floundered, the Gem struck a mine that blew the ship in half. Ten crewmen, including the captain, were killed. Only two, the mate and an ordinary seaman, were rescued by the steamer Altert, they were landed at Wisbech. Six of the ten crewmen killed came from three small villages, Cushendall, Carnlough and Glenarm on the Antrim coast of Northern Ireland. Astonishingly, the tragedy could have been even worse for the villages, as three sailors from Cushendall missed the ship after being delayed at Belfast on their way to join the ill-fated Gem. The sinking still resonates and to mark the centenary of the sinking a play was staged in Cushendall. Among those taking part were family members of some of those killed.

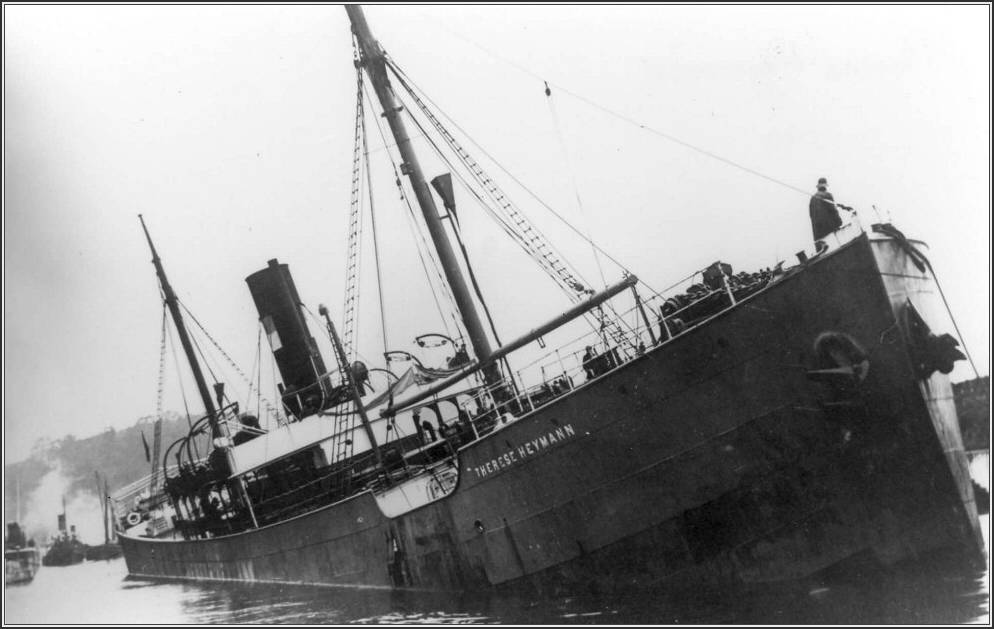

The ship that vanished, SS Therese Heymann, 25 December 1914

The twenty-one strong crew of the Therese Heymann signed on at South Shields Shipping Office on 22 December, she left Tyne Dock at 09.23 on Christmas Day with a cargo 3,060 tons of gas coal for Savona, Italy. A Tyne pilot, John Burn, guided the ship from her berth and left the ship at noon off Sunderland. The ship was never seen again. No wreckage or boats were found, she disappeared without trace. At the official enquiry it was noted that she would have been in the area of the minefield around 23.00 on Christmas Day. It was concluded that she probably struck a mine off Filey.

Crewmen killed on Therese Hayman

William Allardice (23), third engineer, Dundee

Thomas Blakey (41), fireman and trimmer, South Shields

Thomas Brown (35), mess room steward, Sunderland

George Clyne (31), fireman, South Shields

John Cruickshanks (34), first mate, Montrose

Thomas Evans (54), master, Aberarth, South Wales

George Ewart (53), second engineer, South Shields

Albert Hilson (54), sailor, Plymouth

O. Johansen (38), first engineer, South Shields

A. Kesseli (22), sailor, North Shields (born Switzerland)

Frank Large (29), steward, West Hartlepool

Francis Mors (46), able seaman, Sunderland

Walter Manger (45), donkeyman, Dunston-on-Tyne

James Pelper (50), second mate, Sunderland

N. Peterson (26), boatswain, North Shields (born Sweden).

Albert Pikkor (20), fireman and trimmer, South Shields (born Russia)

Oscar Rahikain (22), sailor, South Shields (born Russia)

Robert Robinson (32), ship’s cook, South Shields

John Shilson (41), fireman and trimmer, Ferryhill, Co. Durham

J. Stalberg (23), sailor, South Shields (born Sweden)

George Turnbull (46), foreman and trimmer, Sunderland

The Gem

The Glasgow steamer the Gem was carrying a 460-ton cargo of salt cake from Mostyn to the Tyne. Near where the Eli had foundered, the Gem struck a mine that blew the ship in half. Ten crewmen, including the captain, were killed instantly. Only two, the mate and an ordinary seaman, were rescued by the steamer Alert, they were landed at Wisbech. Six of the ten crewmen killed came from three small villages, Cushendall, Carnlough and Glenarm on the Antrim coast of Northern Ireland. Astonishingly, the tragedy could have been even worse for the villages, as three sailors from Cushendall missed the ship after being delayed at Belfast on their way to join the ill-fated Gem.

Captain H. Rattray of the Middleton described the carnage. His ship had passed Scarborough, about a mile and a half off shore, around him were around twelve to fourteen steamers, all heading south. He stated that about two miles north of Filey Brigg there was such a tremendous explosion that he thought that his ship had struck a mine. However, he saw water flying over the forepart of a Norwegian steamer (Eli), which was inshore of them but only five hundred feet away. Captain Rattray ordered the engines stopped, he noted that the Eli had got her boats away and that they were headed towards a stationary steamer (Alistair) close astern. With the Eli settling quickly by the head, the Middleton crept forward once more. Seconds later there was a double explosion astern of them, another steamer (Gem) seemed to have had her bottom ripped out and she sank rapidly in two sections. The captain said, despite the fact that there were steamers all around the stricken vessel, he feared there would be loss of life due to the rapidity of the sinking and, because it was so cold, no one could survive more than a few minutes in the water.

In August 1980 the wreck of the Gem was discovered in two halves some 150m apart. Diver Pete Lassey noticed a small circular object protruding from the slit, 40m down near Filey Brigg. It was the top of the Gem’s compass binnacle. Weighing 18kg recovering it was a challenging operation. Fellow diver Andy Jackson recalled the conditions as ‘like working in Indian Ink’. Following a week of intensive diving the binnacle was recovered and was placed on display in the club house of the Scarborough Sub Aqua Club for thirty-four years.

Thirty-four years later, with the centenary of the tragedy being planned, people from Cushendall asked the Scarborough Sub Aqua Club if anything had been recovered from the Gem and learnt about the recovery of the binnacle. David Barry, Press Officer Scarborough Lifeboat Station, wrote about the subsequent events:

“They wanted something to commemorate with and asked to borrow it but we insisted on giving it to them,” said Pete Lassey. “We decided they should be the custodians of it.” The binnacle was too delicate to send by courier so the Cushendall development group paid for two members of the community to fetch it. Joe Burns and Danny Beaven, who made the 626-mile round trip to Scarborough over two days, were formally presented with the relic at the diving club.

“You’ve no idea what this means to us,” said an emotional Mr Burns, who has written a play based on the tragedy. The binnacle will be cleaned up and kept at the Red Bay lifeboat station near Cushendall, which is chaired by Mr Beaven. Mr Burns is a deputy launching authority for the Red Bay lifeboat. Four current crew are direct descendants of the men who died. The two visitors presented Scarborough RNLI coxswain Tom Clark with a hurling stick, which he said could double as “a crew controller”. The sinking still resonates in the small coastal villages on the Antrim coast and to mark the centenary of the sinking a play was staged in Cushendall. Among those taking part were family members of some of those lost on that tragic Christmas Day in 1914.

Crewmen killed on the Gem

William Graham, fireman, Glenarm, County Antrim

Duncan McInnes (64), engineer, Glasgow.

James McKeegan, captain, Cushendall, County Antrim

Hugh McKeegan (27), cook, Cushendall, County Antrim

James McNaughton (22), able seaman, Cushendall, County Antrim

Henry O’Dornan (23), fireman, Carnlough, County Antrim

Thomas Simpson (24), second engineer, Glenarm, County Antrim

James Umphray (25), able seaman, Leith

Ted Williams, able seaman, Holywell, Flintshire

John Wotherspoon (47), boatswain, Tarbert, Argyllshire

The Norwegian Collier Eli, 25 December 1914

On Christmas Day the Norwegian collier Eli was outbound from Blyth to Rouen in France with a cargo of coal. Captain Sveen of the Eli said that because of the suspension of shipping in the wake of the bombardment, when he sailed south he was in the company of around thirty other steamers and a number of British minesweepers. Because of the danger of mines, the captain, second mate and the North Sea pilot (Alexander Benson of North Shields) were all on the bridge. The Eli was off Red Cliff, Cayton Bay, when the ship hit a mine. The mine detonated amidships in the bottom of the ship and threw a huge column of water, mixed with coal, higher than the ship’s mast. The captain, second mate and coxswain were all thrown to the floor, whilst the pilot was engulfed in the deluge. Lieutenant Thomas Danielsen was thrown out of his berth onto the roof, he received a nasty blow to the forehead above the eye and passed out. Fortunately, he soon recovered his senses and, with three others who had been in their bunks, they ran on deck in just their underwear. With all the fifteen strong crew, plus the British pilot, in the lifeboats they cast off and had not got far when they saw their ship sink rapidly by the bows. The Eli went down in less than three minutes. The last thing they saw was the Norwegian flag flying from the stern as the Eli disappeared beneath the waves.

The Aberdeen coaster Alistair, en route from Montrose to London, was nearby. They rowed to the Alistair and were helped on board. As they got onto the deck of the Alistair they heard a loud explosion as another ship came to grief in the minefield. Captain Sveen thought that she was a Belgian ship and despite the explosion, she did not appear to be sinking. It was actually the London registered steamer Gallier, en route from Hartlepool to France with a load of coal, that had struck a mine. Although now onboard the Alistair, the crew of the Eli did not feel safe and got back in their lifeboats and were towed to Scarborough. There they were clothed, fed and accommodated by the Shipwrecked Mariner’s Society. Steffen Steffensen, the helmsman, was treated for a nasty blow to the chest, but he soon recovered. The crew of the Eli arrived home in the Norwegian port of Haugesund on New Year’s Day on board the steamer Mira.

In the summer 1971 the wreck of the Eli was discovered in seventy-five feet of water off Red Cliff, Cayton Bay. The bow section was almost intact, aside from a huge hole in her port side which was probably where the mine detonated.